The last two decades of the 19th century were years of tremendous change in American men's and boys' fashions. While these changes were related, they did not appear at the same time, nor did they proceed at the same rate.

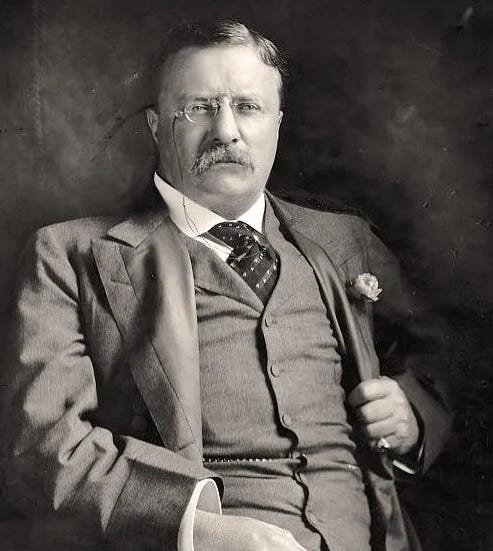

The acceptance of the “sack” suit for everyday business dress, accomplished during the 1880s, was a final act in a drama which had been playing out for at several hundred years. Men's clothing had undergone a very gradual evolution from colorful, individualistic and expressive (see Henry VIII) to drab, conformist and utilitarian (see Theodore Roosevelt).

The same changes had not affected little boys’ fashions. Up through the 1700s, while men’s clothing was being transformed, little changed in the way baby and small children were dressed. Infants -- male and female alike - wore long white dresses until they were old enough to walk. The dresses were then shortened, but white remained the predominant color. Little, if any, distinction was made between the clothing of boys and girls until they were three or four years old. Children past that age had dressed like miniature adults.

Clothing for boys between infancy and puberty was only invented towards the end of the 18th century. Boys' clothing in the 19th century occupied a distinct category of fashion, influenced by women's trends but unique to boys. These tended to be rather fanciful -- pleated skirts with braid-trimmed jacket, velvet suits with collars and trims borrowed from men's styles of earlier times, and other styles "effeminate" to modern eyes, but signifying romanticized masculinity to Victorian parents. The Balmoral-inspired kilt suits worn by the Royal Family were widely imitated in England and America from the 1840s through the 1890s, for example.

As I learned in my dissertation research, by the 1880s, the business suit was well-established as the uniform of the go-getter, and the man of the new century. The older styles such as the frock coat were rapidly being identified with effeminate aesthetes, politicians, and members of the genteel poor, such as college professors and clergymen. This revealed a new puzzle: At the same time that American men were making this transformation, the convention of elaborate, picturesque dress for boys showed no signs of waning. If anything, it seems to have reached its pinnacle in the late 1880s, with the huge popularity of “Little Lord Fauntleroy” suits.

Curious, I turned my attention to the book and its impact.

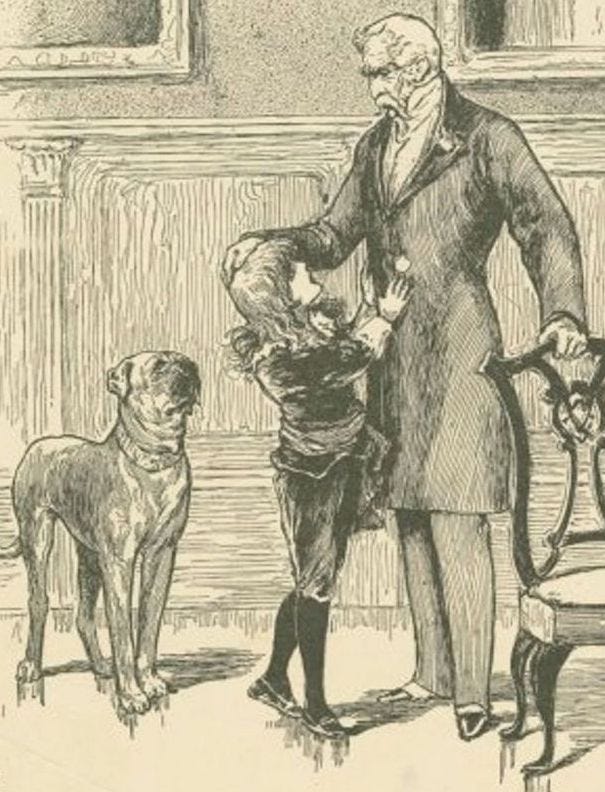

Little Lord Fauntleroy was originally published as a serial in St. Nicholas, a children's magazine, in 1886; a book version appeared the same year. It is a tale of an American boy, Cedric Errol, and his widowed mother, who are summoned to England so that Cedric may meet his paternal grandfather and take his rightful place as Lord Fauntleroy, heir to his grandfather's estate. The old Earl dislikes Americans and refuses to meet his daughter-in-law, insisting that the boy live with him, apart from his beloved mother. Gradually, the Earl discovers that Cedric is a courageous, chivalrous boy with a strong sense of right and duty -- due mainly to the influence of his American mother, who is finally allowed to rejoin Cedric and enjoy the love and respect of her father-in-law.

Cedric's appearance is important to the story, as an outward sign of his own natural nobility. We first meet seven-year-old Cedric running breathlessly down the New York streets, described in the words of a devoted servant: "An' ivvery man, woman and child lookin' afther him in his bit of black velvet skirt made out of the misthress's ould gound.” Later, Cedric wins a footrace wearing a summer suit of cream-colored flannel with a red sash, his long golden locks streaming behind him. In this way, Burnett introduces Cedric as princely yet every inch an active, energetic boy.

The serialized story and the book were a huge success, eventually being translated into twelve languages and selling over a million copies in English alone. By 1893, Little Lord Fauntleroy could be found on the shelves of 72 percent of America's public libraries, second only to Ben Hur.

An important factor in the book's popularity was the stage adaptation, which brought the story to life for audiences in England as well as in the United States. The play opened in London in May 1888, previewed in Boston the following September and moved to Broadway in December of 1888. A New York reviewer wrote, after seeing the preview, "As an ideal picture of child life as 'Little Lord Fauntleroy' has never been sup-posed." Of child actress Elsie Leslie, the first of many females to portray Cedric, another reviewer wrote, "She is a lovely figure in Cedric's dainty costumes and her photograph in character will be in the shop windows before too long." The same writer continued, "Every mother will like the pretty play, the children will be taken to see it, and few fathers will object to it.” Many children were indeed taken to see it; most audiences included large numbers of children, a phenomenon that more than one reviewer noted. By the spring of 1889, the "Fauntleroy" mania had spread throughout the country. In June, there were two New York productions, three companies in Boston and two in Chicago, in addition to at least a dozen more touring companies. Eventually "Little Lord Fauntleroy" played for nearly four years in New York and two years in London.

The Fauntleroy suit enjoyed its greatest popularity in the fall and winter of 1889-90, after the play had reached audiences all over the country. Godey's Lady's Book and Magazine provides a very good description of the style: "For small boys nothing has met with such universal favor as the Fauntleroy suit. It certainly is the most attractive seen for some time. It is usually made of black velvet or velveteen, with a broad collar and cuffs of Irish point lace, with a sash of silk passed broadly around the waist and knotted on one side."

This was an interesting case of life imitating art imitating life, for the cavalier-style velvet suit associated with. little Cedric Errol was based in turn on clothing actually worn by the sons of Fauntleroy's author, Frances Hodgson Burnett. An 1885 photograph of Vivian Burnett in his velvet cavalier suit was sent to illustrator Reginald Birch as a model for his drawings of Cedric Errol.

The velvet suits worn by Vivian and his older brother were similar to dressy outfits which had been acceptable fashions for middle-class boys for at least a generation. Peterson's Magazine described the following outfit in 1865, more than 20 years before Little Lord Fauntleroy was published: "A little boy's knickerbocker suit of black velvet.” During the 1880s, l7th-century-style suits in black velvet (also called cavalier suits) were among the most popular styles for boys from the ages of four to seven or eight. The practice of postponing the first haircut as long as possible added to the "cavalier" effect. For these reasons, it is probably accurate to say that Vivian Burnett was one of thousands of American boys were dressing like Little Lord Fauntleroy several years before the story was published.

Around 1900, boys' fashions began to rapidly undergo a change which echoed that which had occurred in men's dress, only much more dramatic. Skirted styles for preschool-aged boys fell into disuse, as boys were put into knee breeches at an earlier age than before. The sailor suit, paired either with knickers or long trousers, won favor with many families, to such an extent that by the turn of the century, girls' versions were available. So the question in my mind was not “Why didn’t boys clothing follow the simplifying lead of men’s fashions in the 1880s?”, but “Why did it take twenty years?” My answer: it wasn’t the children of 1900 who changed the gender rules in their own fashions. It was their parents, especially their fathers: the boys of the 1880s, with excellent, but less than fond, memories of Little Lord Fauntleroy.

The Fauntleroy suit was not really "universally favored", as Godey's claimed. The boys of America had not been polled, nor had their fathers. Newspapers carried occasional, unsubstantiated rumors of boys deliberately ruining their velvet finery. There is even one story, possibly apocryphal, of an 8-year-old in Iowa who burned down the family barn to protest his mother buying him a Little Lord Fauntleroy suit. When the New York Times polled 400 boys in 1895 about the best books for children, the list included Ivanhoe, The Three Musketeers and several works by Dickens -- but no Little Lord Fauntleroy, despite the thousands of copies which had been sold. After Burnett’s death in 1924, friends and admirers proposed a memorial garden in her honor in Central Park. Though it was eventually created, it was stalled at first by a letter-writing campaign from men claiming that the author had “ruined their childhood”.

Perhaps even more telling is the fate of Little Lord Fauntleroy, when the boys of 1888 reached manhood. Plucky, manly Little Lord Fauntleroy became transformed into a sissy, "chiefly made up of wardrobe and manners", according to Burnett's biographer F.L. Potter. Cedric's name became synonymous with a pretty, effeminate mamma's boy. (Perhaps it didn’t help that in stage and film versions of the story, Cedric was almost always portrayed by a girl or a woman.)

The Burnett character and the clothes he inspired provided a focal point for the rejection of picturesque clothes for boys, not in the 1880s, but much later. In 1889, the name denoted a very specific style, made of velvet and distinguished by a lace VanDyke collar and a broad sash. By 1910, the term was used to describe velvet suits in general, and eventually became a generic label for dressy boys' suits with fancy collars. Conducting interviews with men born around 1920, I found that some referred to fancy sailor suits of the World War I era as "Fauntleroy suits" (in one case, "those damn Fauntleroy suits").

But thanks to little Cedric, the Paoletti Theory of Generational Fashion Change* began to take shape. To understand fashion, dress historians needed to stop looking at at what young people wear over a span of time, and look at what they wore over their lifetimes. Children’s clothing, I thought, might hold important clues to what adults wore when they grew up. How they dressed their own children might then reveal a cultural dialectic that is too often dismissed as nostalgia.

Down the rabbit hole I went.

*Yes, I know I said I didn’t intend to be a theorist. That was true. But it happened, anyway.

Next week: and what a rabbit hole it was!