Simple words for complicated ideas

Semantic wanderings about sex roles and gender in the late 1970s

In my last installment, I told the story of my PhD thesis defense. The committee had agreed that, while the dissertation was excellent, I had not delivered what I promised in the title: “Changes in the Masculine Role in America, 1880-1910: A Content Analysis of Popular Humor about Dress”. See the difference? Not “image”, but “role”. The committee members unanimously agreed that the thesis was about “image” not “role” or “sex role”. Oh,no! I saw winged dollar bills flitting away to my typist’s bank account, like in old cartoons. “So just change the title”, someone suggested. Done. Relief. After all, what difference does a word make? Did the choice of word matter?

I worry that this may be too nerdy, but it’s how I roll.

A close analysis of the dissertation reveals an intriguing pattern in my word choice. I examined my use of the terms “image” and “sex role” (or just “role”, where sex is implied, as in “masculine role”). Only in one section did I use “sex role” more often than “image”: the chapter drawing on the psychological literature. So my own choice of words suggest that the dissertation was about the masculine “image”, not the masculine “role”. Score one for the committee

But wait. What is the relationship between one’s “sex role” and one’s “image” as a male or a female? Which one is included in the concept of “gender”? The answer is far more complicated than it sounds, particularly meaning of the word “gender” is complex and has been morphing continuously since its emergence in the 1970s. I’ve been riding that wave for as long as it has been in existence, hanging on for dear life.

That moment in gender studies:

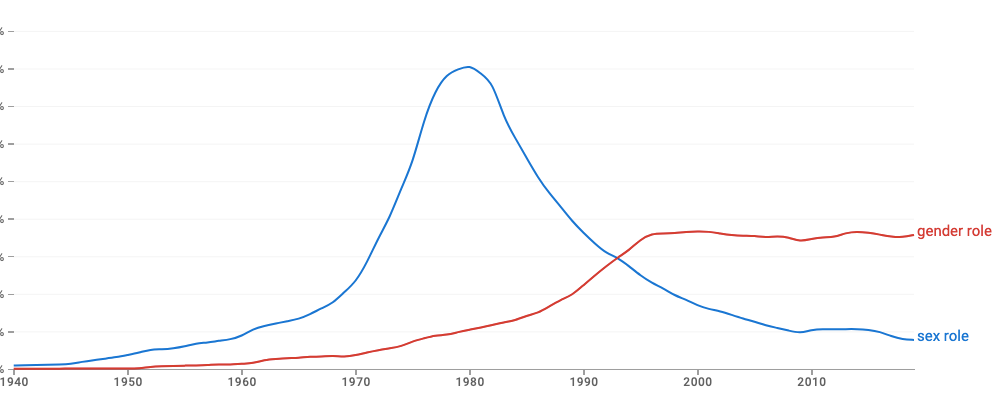

This Google n-gram compares the use of “sex role” and “gender role” in books published over the last seventy years. Note what was happening around the time I was writing my dissertation: the term “sex role” was beginning what was eventually a huge decline, eventually being overtaken by “gender role” in the mid-1990s.

This transformation of the language is illustrated in the current description of the venerable academic journal, Sex Roles:

“Articles appearing in Sex Roles are written from a feminist perspective, and topics span gender role socialization, gendered perceptions and behaviors, gender stereotypes, body image, violence against women, gender issues in employment and work environments, sexual orientation and identity, and methodological issues in gender research.” (Wikipedia)

Compare that with the goals of the journal articulated in its first issue in 1975:

“Sex Roles is devoted to publishing both empirically based and theoretical articles that are relevant to sex-role socialization and change in both children and adults. We will particularly welcome new data dealing with the basic processes underlying the transmission of sex-role information, the cultural determinants of particular sex-role structures and attitudes, and the consequences of such structures upon individuals, relationships, and societal institutions.

I used the term “gender” just eleven times in my dissertation, compared with dozens of instances of “sex role”. In four instances, I used “gender” as a synonym for biological sex, as is common in everyday usage today. When I did use the term “gender” in the sense of socio/culturally expected traits (which I did four times), it was only in the context of Sandra Bem’s instrument, the Bem Sex Role Inventory. That’s pretty interesting, given that Bem herself never used the word “gender” in the 1974 article I cited in my bibliography. I will have more to say about the BSRI and how it shaped my early work in a later essay.

But back to the riddle in my title. Let’s assume that by “role” in the original title I meant what was becoming “gender role”. At that moment in August, 1980, substituting “image” was an uncontroversial fix. If the committee wanted it, let it be so. Just give me my degree and pop open the champagne.

But a more contentious Jo might have asked:

What is the relationship between the roles we play and the images we adopt for those roles?

Focusing on masculine images in the title implies a certain superficiality. Did the roles men were expected to enact change in the late 19th century or not?

Did I successfully connect images and roles in my dissertation?

Should I have changed the title?

Next week: Professor Jo casts a critical eye on her own dissertation and wonders when “gender” became a noun.