Pink and Blue, still.

Knowing that color-coding babies is a recent invention is interesting, but it’s more important to understand why it started in the first place, and how it works to teach gender roles to children.

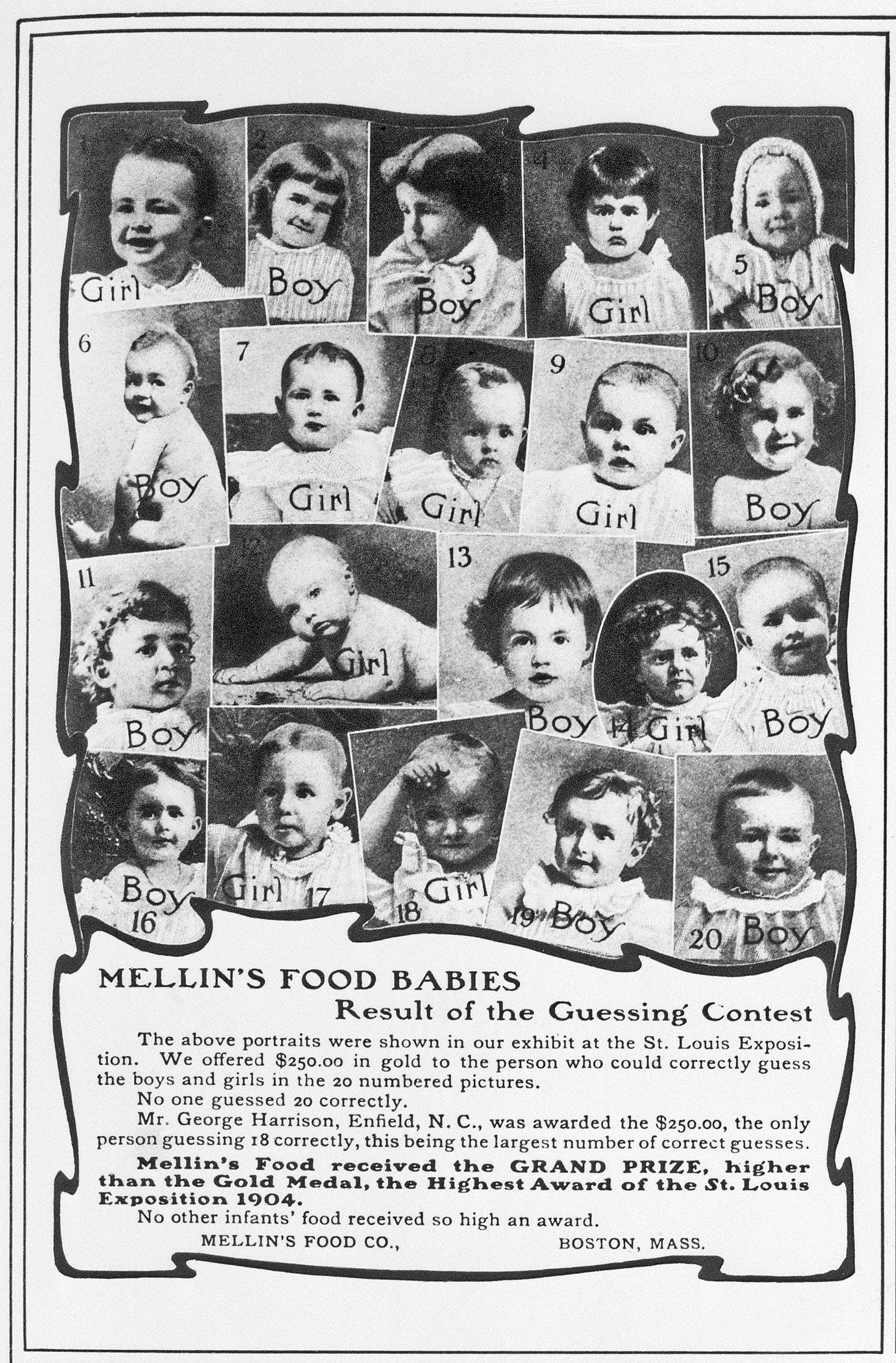

Did you know that pink was sometimes the “boy” color? I didn’t, until one day in 1986, I found this:

Forty years, several academic articles, two books and scores of media interviews later, more people know that pink and blue gender coding is not an ancient tradition. This is probably thanks to all those interviews, from the very first one (by the amazing Peggy Orenstein in the New York Times, in 2006), to the ones I did when Barbie came out last summer. That’s progress, I guess, but not exactly the outcome I had in mind. So here is one more attempt to explain why this matters. Wish me luck.

Knowing that color-coding babies is a recent invention is interesting, but it’s more important to understand why it started in the first place, and how it works to teach gender roles to children.

.

For centuries, babies in Europe and North America (the European colonies, that is) wore white. Not just white, but white dresses. All the babies. They wore white dresses until they were several years old. Why? Because it’s easier to change a soiled diaper if baby is wearing a dress? That’s actually still true. Because white cotton or linen is easier to wash and whiten, either in the sun or using bleach? Also still true. So why aren’t babies and toddlers of all sexes still wearing white dresses? (And yes, I do mean all sexes. Look up “intersex” and educate yourself before you start quoting Genesis. Please).

Parents in the twentieth century started preferring gendered clothing for their children because they were convinced by a new breed of experts - psychologists like Sigmund Freud and G. Stanley Hall - that sexual identity, sex roles, and sexuality were learned in infancy. Hall wrote articles in popular magazines arguing that homosexuality (especially in males) was the result of too much feminine influence in their upbringing (domineering mothers, weak fathers) and advised that distinguishing between boys and girls would counter that influence, and the earlier the better. It took several generations to completely eliminate the white dresses, but if a baby boy wears one today, it’s likely to be an heirloom christening gown and only worn for a few hours.

Before I explain why this matters, I need to offer my usual disclaimer: I am a historian, not a psychologist. What you are about to read is based on the current understanding of how children learn gender roles. It would be a very bad idea to test this using controlled experiments on actual children, so this is the best we can do.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the history of gendered colors is that they were adopted first for infants, and gradually applied to older children and eventually adults. Babies and toddlers can perceive these color differences as early as five months and can apply gender stereotypes by the age of two. All children (except the 8% of boys and 1% of girls who are color blind) learn pink and blue as gender markers. This means that associating pink with girls and blue for boys has been the earliest lesson in gendered visual culture for millions of us. We didn’t just learn the rules for our own sex, and girls and boys don’t learn them in exactly the same way. I believe that girls learn to admire and even emulate boys, and are rewarded with praise for doing it well. Boys learn to see everything associated with girls as a threat to their very identities. If all we need to protect the fragile masculinity of boys is a visual culture that signifies GIRL so clearly that no child under the age of six months will ever mistake one for the other, why do we need blue? In some ways, we don’t; we just need not-pink. Functionally, pink and blue are not opposites.

Pink identifies “girly culture” for all children. For girls, the message is “This is for you, because you are a girl”. For boys, the message is “This is only for girls; don’t touch!” Blue has never played the same role. Girls can have things that are blue; they get the message that girls can do boy things, if they like. A certain amount of “tomboyish” behavior is often encouraged and complemented. For boys, a knowledge of girly culture is required to avoid being teased, bullied, and even physically abused.

For the last century and a quarter, we have believed that gender is learned. Early twentieth century parents wanted less feminine clothing for their sons because they believed it was necessary to teach them to be masculine. Parents in the 1970s believed gender identity was learned to the point where they tried to program their children into new gender roles through unisex child rearing. Some parents today insist on gendered clothing because they believe gender identity is learned, and they want their children to learn “traditional” gender roles.

What if they are all wrong? What might be the unintended consequence of four generations of gendered clothing based on a binary model? When boys and girls can distinguish between each other by the time they start preschool, how does it affect their view of each other?. Does this encourage or discourage same-sex play? Encourage or discourage belief in gender stereotypes? Does it encourage or discourage gender disparities in the wider society?

What if gendered clothing serves no positive, practical purpose for most children? Primatologist Frans de Waal, in Different (2022) argues that some gendered behaviors may be linked to biological sex. For example, female chimpanzees and bonobos, our nearest relatives, share female human babies’ fascination with faces and with cuddling babies or dolls. Male humans are more likely than females to engage in more energetic and even mock-aggressive play, just like their great ape counterparts. It is likely, he argues, that cultural gender norms serve the purpose of reinforcing gender identity, but only in cisgender children. It is unnecessary to teach most children to behave according to their sex; the cultural patterns they see around them will do the job, as was the case for generations of children before Sigmund Freud and G. Stanley Hall told us otherwise.

If he is right, how do we deal ethically and justly with our children who do not experience congruity with their assigned sex? (Please do look up “intersex”, if you haven’t yet.) Regardless of the labels used to express their physical and psychological experiences of identity, - intersex, agender, transgender, nonbinary -- it cannot be helpful to coax or bully them into “normal” behavior. In fact, it could be harmful. What if gendered clothing creates anxiety in gender variant children? What if it also primes children to police and punish any attempts to cross the line? (Kids are very, very good at this!) What if those well-trained children grow up to be homophobic and transphobic adults? I think we know.

And for the record, I am not sure that my interpretation of how gendering works is close to accurate. Still working on understanding...