I am a snoop. My father had a number of nicknames for me based on my sneakiness and insatiable curiosity. I opened and re-wrapped presents, then feigned surprise on Christmas morning. I knew where his Playboy magazines were hidden, and the old letters from his girlfriend. Curiosity is not such a bad trait; it’s kept me going through long hours at the Library of Congress, cranking away on microfilm reading machines. It can be a mixed blessing, though, as it was when, as acting chair of my doomed department, I had access to all the personnel files, including my own.

One point in my favor: I had no interest in anyone’s file but my own. All I wanted was to read my recommendations, to know what other people wrote about me “in confidence”. As it turned out, they all wrote very nice, ego-boosting things about me, which helped assuage the guilt I felt for (still) being such a snoop. Two paragraphs from one reviewer were unsettling, and have haunted me ever since.

The author was one of giants in textiles and clothing scholarship. She devoted two single-spaced pages to my publications and professional service, and then dropped this:

Personally, I am especially delighted that she knows how to handle the infiltration of nineteenth century theories of social evolution into everyday theories of dress. Such has not been true of a number of costume historians who have passed along, perhaps unwittingly, fragments of evolutionary theory as “theories” that explain why people dress as they do.

Although Dr. Paoletti does not explicitly state this is her goal, I believe her work is leading to important and easy to understand theoretical formulations. Thus, I perceive a nascent theory of fashion taking shape, as one of her studies clarifies how changes of dress of men late in the nineteenth century were related to concepts of masculinity, and another reveals that democratization of fashion in about this same period was a matter of consumer choice.

Why did this praise make me feel so uneasy? Simple. I have always had an uneasy relationship with theory. Yes, I had read and could apply theoretical concepts. In my dissertation on men’s clothing, I had reviewed the scanty research on men’s clothing motivation, and even cautiously applied their theoretical interpretations to my results. In the “democratization” paper, I had used the notion of “consumer sovereignty” to fashion change. But the creation of a new “theory of fashion” was never my intent, and still isn’t. (Though now I am thinking about it, at least.)

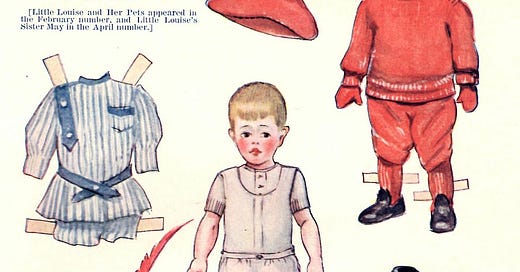

For most of the decade after I finished my PhD, I was consumed by two major efforts: birthing and raising two children and publishing five (yes, 5!!) articles a year in order to achieve promotion and tenure. I am sure someone more theory-oriented could have penned a think-piece or two under those circumstances. But I was simply gathering data from primary sources, trying to figure out what the hell was going on, and cranking out a report of my findings as quickly as possible. Need proof? My 1985 article in Signs*, which was my first and most influential publication outside the clothing and textile cloister, cited twenty sources. Three were my own previous works. One was Suiting Everyone, the companion book to the landmark Smithsonian exhibit on the industrial revolution in the clothing industry. All the rest were primary sources: magazines, newspapers, and mail-order catalogs. No sex role theory, no nod to feminism, just description of “Children's Fashions, 1890-1920”.

I concluded, as I often did, with questions:

“Did American parents decide that they preferred their little boys to look "more masculine"? What role did clothing manufacturers play in this transition? Did they set the trends or were they changing their product to reflect their customers' changes in taste? What role did fathers' memories of their boyhoods-preserved in family photographs for all to see-play in this swift defeminization of boys' clothing? Was the masculinization of boys' and men's clothing a reaction to more androgynous styles for women and girls?…How did this trend respond to later forces, such as the post-World War II emphasis on sharp distinctions between masculinity and femininity? To what extent is the androgyny of contemporary American fashion reflected in the way in which we dress our own children?”

Eventually, those questions did lead me to a clearer understanding of children’s clothing history, but never to my tenure reviewer’s hoped for “new theory of fashion”. Instead I opened the door and found: Little Lord Fauntleroy.

*Paoletti, Jo B. "Clothing and Gender in American Children's Fashions 1890-1920 " Signs 13:1 (Autumn 1987): 136-143

Next week: What Little Lord Fauntleroy taught me about gender.

Interesting. I do not have children, but considering their rough and tumble play, I would be more concerned about how clothing withstood real life rather than its appearance or gender significance.

There were clothing items that required such careful washing, ironing, and frequent repairing!